Introduction

This is not a tutorial. This crash course is a quick way to get started making a basic Django website without going in-depth about the underlying concepts that are required to make complex web applications. For every step of this crash course I will link a more thorough explanation of the tools and concept you’re using, so you can get a better understanding of Django while creating your first project.

Prerequisites

Basic Python, HTML , CSS and Unix Command Line. As long as you’re comfortable with all that, you’re good.

Our Goal

We’re making a website where you can upload an image with a title, date and description. Simple.

So, what is Django?

Django /JANG-oh/ — A type of tool (web framework) most known for helping people make neat websites quickly with few mistakes.

Making stuff in Django follows this pattern:

- Model — How you store stuff. This is where we will tell Django how to store our images, titles, dates and descriptions.

- View — Where your project thinks. This is how our website will get the stuff we stored based on our models and process it for the user.

- Template — How your project presents the stuff it was thinking about. The view will use this to display the contents it processed based on our models.

Django does more complex (and really fun) things, but if you’re starting out that’s all you need to know for now . [in-depth]

Setting up our project

Notice for Windows users:

By default, Windows doesn’t have a Unix command line, which is a prerequisite for this

crash course. The October 2018 update for Windows 10 offers Linux subsystems, such as Ubuntu. Please install and set up

a Linux subsystem to utilize the Unix command line.

We’re going to use your computer’s terminal to set up our python environment and Django. Let’s make the project in our

computer’s Documents folder, so enter these commands:

cd ~/Documents

python3 -m venv django_ccpython3 -m venv django_cc will create a virtual environment within a folder called django_cc for our project, so all

the stuff we install for it to work won’t interfere with anything else on your

system. [in-depth]

Next we’ll get in our project folder, enable our new python environment and install Django.

cd django_cc

source bin/activate

pip install djangosource bin/activate will activate the virtual environment we created. This means when we install Django, it won’t be

installed on the whole system, just in our project. pip install django will use Python’s package manager to install

the most recent version of Django.

Now that Django is installed, we get some new commands. Let’s start by creating a project within Django, migrating our development database and finally starting our local development server for the first time to ensure we did everything right.

django-admin startproject django_cc

cd django_cc

python3 manage.py migrate

python3 manage.py runserverdjango-admin start project django_cc is telling Django to make the stem of our project where everything else will be

connected (i.e. Django apps). This is also where we will find manage.py the file that we will use to interact with

Django. [in-depth]

python3 manage.py migrate is used to let Django know that changes have been made to our models. Since we’ve just

started our project this will be our initial migration which establishes models Django makes on its own (i.e. accounts,

activity logs, permissions, etc.). [in-depth]

python3 manage.py runserver will start our development server where we will be testing our project.

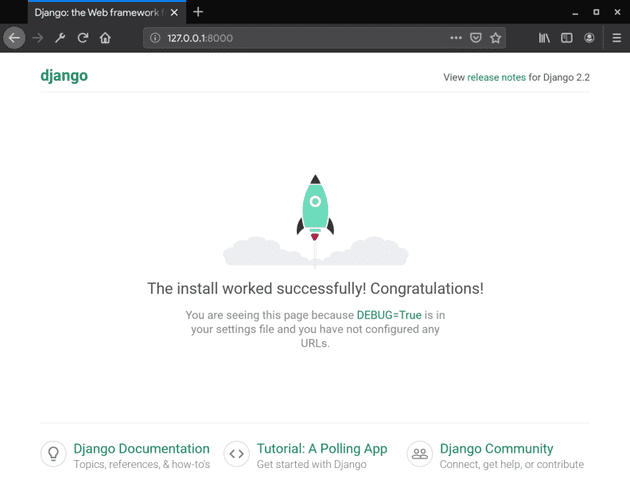

To see the development server in action, go to 127.0.0.1:8000 in your browser. A Django start up page should appear:

The Database

Next, grab your favorite text editor or python IDE because we’re going to delve into Django. We’re going to start by creating a Django app where we will write all of our models for this project.

python manage.py startapp blogIn order for our core project to recognize this app, we need to let it know our blog app exists by adding it

to INSTALLED_APPS in django_cc/settings.py like so:

# Application definition

INSTALLED_APPS = [

'django.contrib.admin',

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.messages',

'django.contrib.staticfiles',

'blog',]Media file support

Let’s add the following to the bottom of settings.py so Django knows where to store media files such as the images

that we upload:

# Media file support

MEDIA_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'media')

MEDIA_URL = '/media/'We’ll need to do the same for our templates folder by updating DIRS to handle [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'templates')]

instead of the default []:

TEMPLATES = [

{

'BACKEND': 'django.template.backends.django.DjangoTemplates',

'DIRS': [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'templates')], 'APP_DIRS': True,

'OPTIONS': {

'context_processors': [

'django.template.context_processors.debug',

'django.template.context_processors.request',

'django.contrib.auth.context_processors.auth',

'django.contrib.messages.context_processors.messages',

],

},

},

]We will also need to add a few imports and a conditional at the bottom of django_cc/urls.py so the files are

accessible on the development server:

from django.conf.urls import url

from django.contrib import admin

# Add these imports for static file support and to get

# directory details from Django's settings.py

from django.conf.urls.static import static

from django.conf import settings

urlpatterns = [

url(r'^admin/', admin.site.urls),

]

# Add this to enable media file support on the development server

if settings.DEBUG:

urlpatterns += static(settings.MEDIA_URL, document_root=settings.MEDIA_ROOT)Great, our project is now set up, and we can begin by writing our models.

Writing our models

Inside our new blog app, we will find a models.py file where we will write our models for our database. The

class Post will act as our first model for uploading a post with an image, title, description, and date published.

from django.db import models

import datetime

class Post(models.Model):

image = models.FileField(upload_to='images/')

title = models.CharField(default="", max_length=64)

description = models.CharField(default="", max_length=512)

date = models.DateField(default=datetime.date.today)models.FileField(upload_to='images/') acts as a field where we will upload images to an image folder in the media

directory we configured in settings.

models.CharField(default="", max_length=n) is a basic text field where the max character length is n.

models.DateField(default=datetime.date.today) is self-explanatory, it’s a date/time field that is set to the current

date and time.

To finish off our models, let’s tell Django to order them based newest to oldest:

class Post(models.Model):

image = models.FileField(upload_to='images/')

title = models.CharField(default="", max_length=64)

description = models.CharField(default="", max_length=512)

date = models.DateField(default=datetime.date.today)

class Meta:

ordering = ['-date']

def __str__(self):

return self.titleThe Meta class can do a lot, in our case we will use it to order our models based on time. The __str__ function is

telling Django to display the title (instead of saying Post 1, Post 2, etc.) for when we interact with our entries later

in the Django admin panel. [in-depth]

Migrating our new models

Finish off our models with the following two commands that essentially tell Django that we’ve made some changes and that they should be applied to our database:

python3 manage.py makemigrations

python3 manage.py migrateCongratulations! Our database is all set up for our posts. There is one issue, though. We can’t edit them right now. Let’s get you set up with the Django admin panel, so you make some posts.

Admin control panel

Inside our blog app, go to admin.py and add the following:

from django.contrib import admin

from blog.models import Post

admin.site.register(Post)from blog.models import Post imports all the models that we’ve just created. admin.site.register(<model_name>) tells

Django to display that model within the control panel.

Next, we will create a superuser, so we can log into the admin panel. Type the following command and follow the prompts. You only need to fill out the username and passwords prompts.

python3 manage.py createsuperuser

Username (leave blank to use 'ari'):

Email address:

Password:

Password (again):

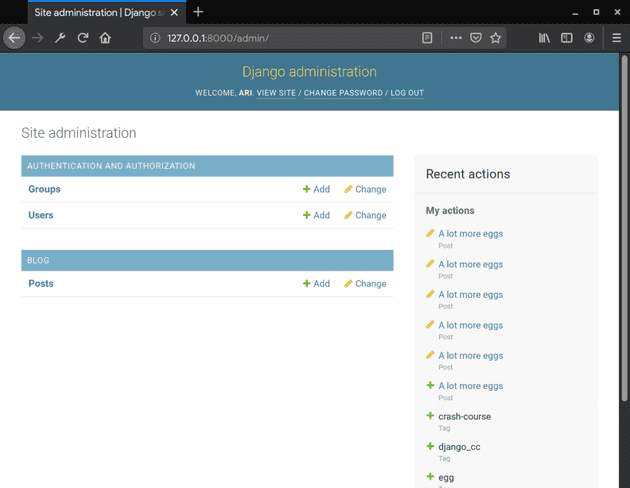

Superuser created successfully.Once completed, head over to 127.0.0.1:8000/admin and sign in with the credentials you just wrote. You should see this page:

From here you can add posts to your Django project. We are officially done with our models. Next will design our view so Django can serve our posts.

View logic

A view is how Django knows what to do when we ask for a page. The first thing we have to do is create a views.py file

in django_cc. In that file, paste the following:

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.views.generic.base import View

from django.views.generic import TemplateView

from blog.models import Post

class PostFeed(TemplateView):

template_name = 'index.html'

def get_context_data(self, *args, **kwargs):

context = dict()

context["posts"] = Post.objects.all()

return contextfrom django.views.generic import TemplateView allows us to use Django’s basic template view which is all that we need

for displaying our posts. from blog.models import Post imports all of our database models for our view functions to

use.

PostFeed is our basic template view that will use an index.html file we will create next to render our database

contents.

get_context_data is how we will send our template the information from the

database. context["posts"] = Post.objects.all() Our template will refer to posts within our context dictionary for

a list of all posts that is collected from the database using Post.objects.all()

In urls.py we will need to add a new path so Django knows when that URL is requested to call our view:

from django.conf.urls import url

from django.contrib import admin

from django.conf.urls.static import static

from django.conf import settings

# import path for easy urls

from django.urls import path

# import our views so urls.py can call them

from django_cc.views import PostFeed

urlpatterns = [

# Path for root of our website that will display the post feed

path('', PostFeed.as_view(template_name="index.html"), name="PostFeed"), url(r'^admin/', admin.site.urls),

]

if settings.DEBUG:

urlpatterns += static(settings.MEDIA_URL, document_root=settings.MEDIA_ROOT)Our basic view logic is now complete, now we need to build our index template for displaying our posts.

Templates with Style

In the root of our Django project where you can find our blog and django_cc folders, create a templates folder and

make an index.html file inside. For the design of our site, we’re going to use the

framework Bulma so we won’t need to write any CSS. Here is a boilerplate we can use

for our template.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Posts | Django Crash Course</title>

<link

rel="stylesheet"

href="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/bulma/0.7.4/css/bulma.min.css"

integrity="sha256-8B1OaG0zT7uYA572S2xOxWACq9NXYPQ+U5kHPV1bJN4="

crossorigin="anonymous"

/>

</head>

<body></body>

</html>Django templates utilize a DRY version of HTML called Django HTML. This is how we will send our context to render in

our index.html template. In the body of the boilerplate, let’s add a basic card with the context for our posts.

<div class="container">

{% for post in posts %}

<div class="card">

<div class="card-image">

<figure class="image">

<img

src="{{ post.image.url }}"

alt="Placeholder image"

style="max-width: 250px; max-height: 250px;"

/>

</figure>

</div>

<div class="card-content">

<div class="content">

<b>{{ post.title }}</b> | {{ post.description }}

<br />

<time datetime="{{ post.date }}">{{ post.date }}</time>

</div>

</div>

</div>

{% endfor %}

</div>{% for post in posts %} acts as a for loop that will duplicate its contents for each post inside posts.

Every time the for loop runs, the context for the post in the current iteration is placed in the HTML when it is referred

to using {{ <variable> }}

{{ post.image.url }} is how you refer to the image’s URL, you cannot just reference the image itself.

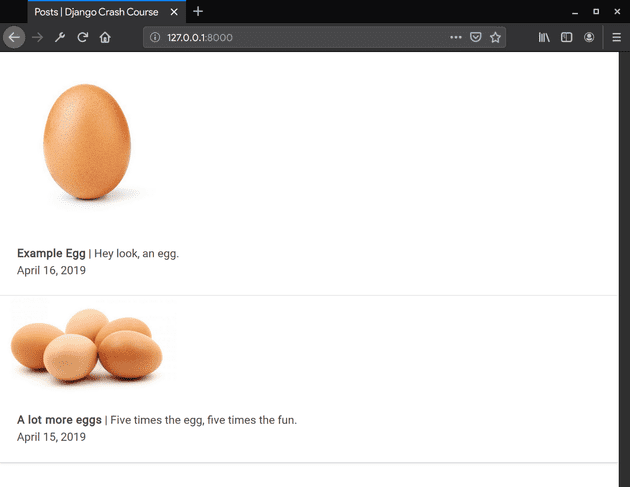

When we visit 127.0.0.1:8000 there should be a list of all the posts we’ve added in the control panel:

Now we have a website that displays what we add to our control panel in Bulma cards. Neat.

Wrap Up

Django is a wonderful framework for building websites and other complex things. Today, you’ve created a very basic website that is capable of displaying posts akin to Instagram and in the future hopefully you can build Instagram yourself. For now, I suggest learning more about Django either through their documentation or this introduction (which got me started).

FYI — Follow this tutorial by DigitalOcean so, you can learn how to host your Django creations for the world to see.

Edit: Renamed classes to adhere to PEP 8 and renamed database app to blog.

Edit: Fixed return context, settings.py template directory issue and references to blog models. Thank you, Chris

Merck for the feedback.